Welcome to our website – we are a group of historians, anthropologists, political scientists and activists based in Shanghai and Pondicherry committed to fostering exchange on pressing ecological and livelihood issues in and around the Indian Ocean. By bringing together already existing research teams working on port cities and the littoral environments in India and China , we seek to generate a much needed transnational conversation on issues of infrastructural redevelopment, technological transformations, environment sustainability, commoning and coastal livelihoods. We understand the title “Archiving coastal lives’ as a deeply intellectual and political project to recover histories of spaces, objects, memories that have been typically hidden by the official state and corporate archives. Our focus of study is the Coromandel coast.

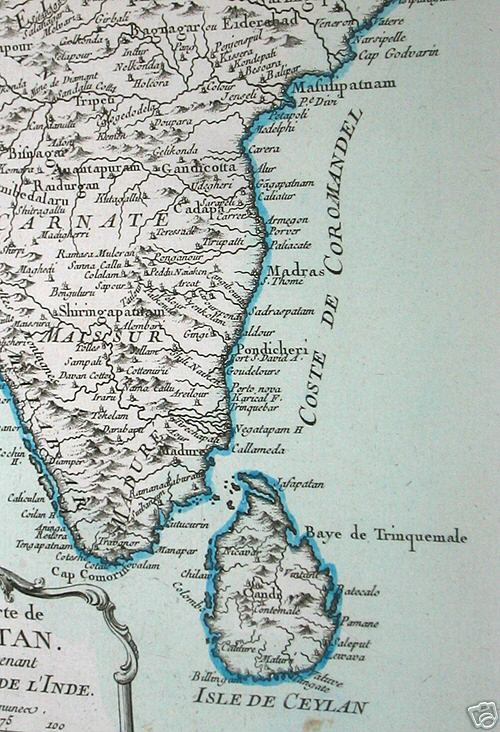

From a detailed map by J. Covens and C Mortier : ‘Carte D’Une Partie Des Indes Orientales’, Amsterdam 1740

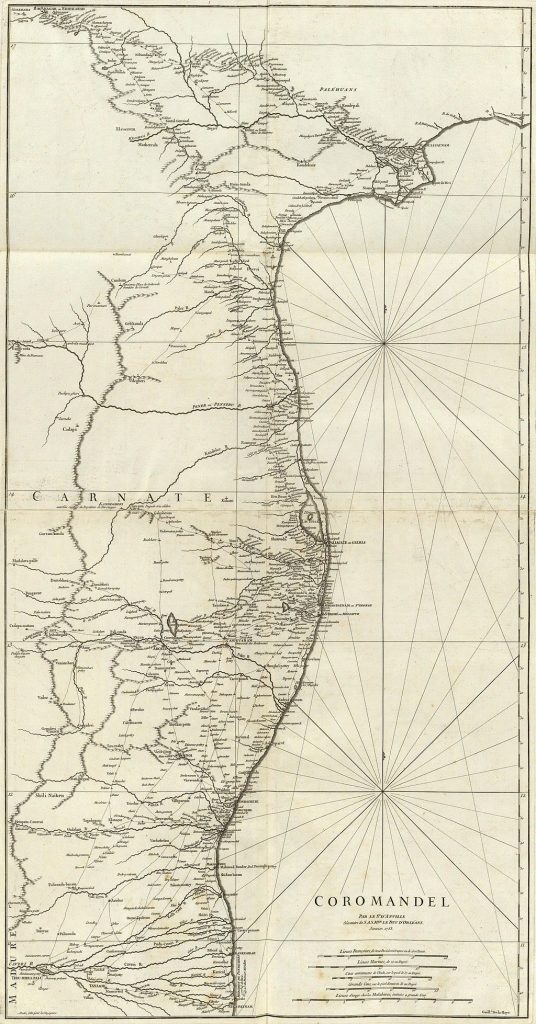

A 1753 French Map of the Coromandel Coast

“A New and Accurate Map of the Northern Coast of Choramandel in the East Indies,” for the London Magazine, 1757

Over the centuries Nestorian merchants and Arab navigators, Greek philosophers and Roman centurions, ‘Portugee’ hidalgos and Dutch burghers, English East Indiaman and French musketeers, even Danish sailors and German scholars descended on Coromandel’s ancient shores in search of diamonds and pearls, ivory and sandalwood, cordage and sails and, above all, the finest cottons in the world.

These were the riches of a great hinterland where for centuries ancient kingdoms had risen and fallen and risen again. To the South lay the maritime Pandya and Chola kingdoms, possessors of an amazing artistic legacy. To the West were the Pallavas, who had absorbed the skills of the Chalukyas and the Hoysalas and sculpted veritable open air museums. To the North were the last vestiges of Vijayanagar and the southernmost outposts of the Mughals. Their nayaks and nawabs added the final touches to the endless wealth of art, craft and skill that thrived in Coromandel’s hinterland.

Muthiah From the first city of Modern India

From a map by Rigobert Bonne, from Raynal’s ‘ Histoire philosophique et politique des Europeens, 1774

The Coromandel coast is the southern part of India’s east coast. It extends over an area of about 8,800 square miles (22,800 square km), bounded by the Utkal Plains to the north, the Bay of Bengal to the east, the Kaveri delta to the south, and the Eastern Ghats to the west.

Charles Allen in his book ‘Coromandel A Personal History of South India has this to say about the origin of the term:

So Coromandel takes its name from the ancient dynasty of Tamil rulers known as the Chola. That word Chola first appears on rock inscriptions that can be accurately dated to within a year or two either side of 260 BC, carved by order of Emperor Ashoka, and it continues to reappear century after century on the walls and monuments of the great temple cities of Tamil country, right up to a final appearance in the year 1279 CE.

The Coromandel Coast and Ceylon, by an unidentified cartographer, c.1790

First coined by a young Italian adventurer named Ludovico Di Vartheme in his text Itinerario, the term Coromandel was initially used by the Portuguese in their maps to travel to India’s eastern sea coast. With the subsequent translation of Ludovico’s text from Portuguese to English, other trading European companies also came to know about the region and began to establish their dominance. In 1609 the Dutch outbid the Portuguese and captured their fort at Pulicat or Pazhaverkadu which is currently known for its bird sanctuary. In 1690 the Dutch East India Company shifted its headquarters from Pulicat to Nagappatinam and continued to control until 1781, when it finally fell to the English East India Company. From the last decades of the eighteenth century the Coromandel coast became the focus of the European maritime powers and played a dynamic role in the political and commercial activities of the Indian region till the early 20th centuries.

Coromandel coast – home to several flourishing ports and a transoceanic commercial trading economy in the colonial period has witnessed significant transformations in the present day as well. It has been the site for several economic, legal and infrastructural projects undertaken by the post-colonial state to initially develop and modernise the small fishers and later on transitioned to the construction of boatyards and harbours. From the 1950s onwards the region has seen the introduction of several port led modernisation initiatives such as the building of physical infrastructures, containers, large scale mechanised boats, ring seine boats, marine fisheries and spatial zoning of the coastal commons. These initiatives have adversely affected coastal environments and livelihoods. Mega infrastructural projects which brought together far flung financial institutions, public and private stakeholders expertise and planning have sold modernist dreams about greater connectivity, economic growth and prosperity while forcing the coastal communities to negotiate the catastrophic consequences of ecological balance, disruption of livelihoods, abandoned projects and ruination.

For too long our imagination of the sea and the coasts have been hijacked by the spectre of harbour development and the promise of a globally integrated economy. We believe that coastal communities caught in the violence of the physical and social detritus created by different infrastructural and capital intensive projects are in need of an archive – a community digital archive that would not drown their voices under the weight of false promises and claims about development. By a community digital archive we define a process of knowledge production not limited to the retrieval of bureaucratic truths. Typically archives are understood as monumental sites of knowledge production by the state. By design they are meant to legitimise state power and exclude the unlettered subaltern (Stoler 2002; Povinelli, 2011; Subramaniam 2016). Similar elisions are also visible in the post colonial corporate and state archives where the focus on establishing the ascendancy of technical reason and rational calculations has excluded or silenced community voices. Against these dominant state and corporate led archival practices which have reduced coastal populations to developmental targets or collective statistics, our project is an attempt to capture memories, the heterogeneous and uneven experiences of modernization processes and restore agency to these communities. Given our approach to recover coastal histories from some of the present day ideological and rhetorical claims about progress and development, we also draw from recent interpretations which have moved away from idealised notions of infrastructure-led expansion. Infrastructures are liable to fail, to fragment and here literature on the material foundations of unfinished infrastructures, debris, structural ruins are useful to understand the continuous process of ruination and the impact of the physical transformations of the shoreline on coastal livelihoods.

The ethical core of this collaborative project lies in its emphasis on building an archive that is accessible and shaped by the practises and concerns of the coastal community. Such an approach will question the privileged monopoly of the experts in the production and consumption of knowledge and reverse the operation of cultural and epistemic hierarchies built into the process of knowledge production. Instead of transforming the community into an anthropological other as is often the case with conventional archival exercises, we endeavour to deeply embed ourselves within some of the ongoing community level projects to record narratives of displacement and loss of livelihoods and develop an archive through broad based dialogues with scholars in Pondicherry, community activists, literary figures and practitioners. For this we derive inspiration from caste and race studies which have effectively mounted a critique of such scholarly mediations of subaltern experiences and developed models of knowledge production that have enabled subalterns to access their own reality.

Funding

Archiving Coastal Lives is a non commercial project. It has received funding from the Henry Luce Foundation and is part of a three year on-going research project on Asian littoral environments based at New York University Shanghai.

CONTACT US

Email: shanghai.cga@nyu.edu

Phone Number: +86 (21) 20595043

WeChat: NYUShanghaiCGA

Address:

Room W822, 567 West Yangsi Road,

Pudong New Area, Shanghai, China

© 2024 All Rights Reserved