China’s archaeology is rapidly going global. Can you briefly introduce the developmental trajectory and current situation of China’s archaeological work in countries along the “Belt and Road”? What are the areas of focus and representative work?

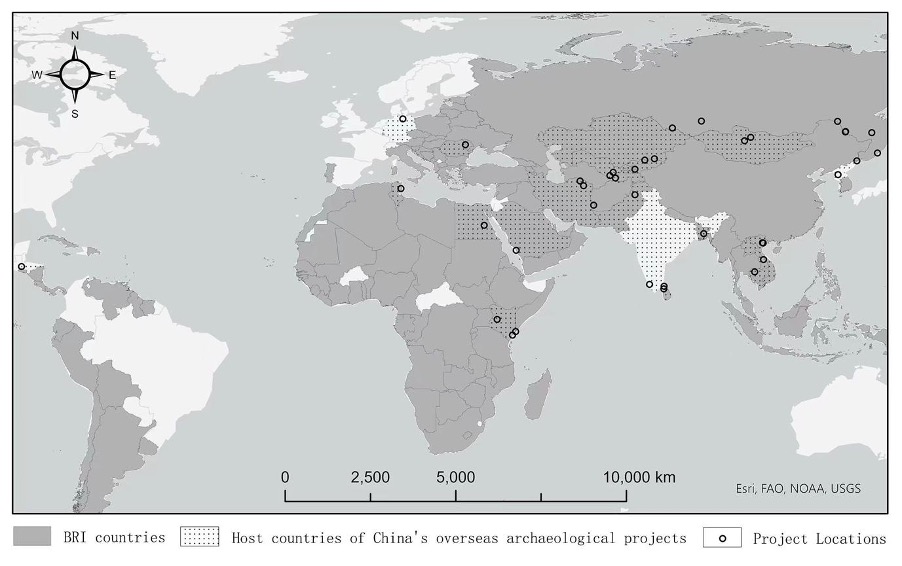

Generally speaking, China’s involvement in archaeological investigations along the “Belt and Road” parallels the development of its overseas archaeology. The reason for this is that, except for a few countries such as India and North Korea, all countries in which we have carried out archaeological investigations have joined the BRI. The developmental trajectory of China's overseas archaeology involves three stages, divided by the BRI proposal and the outbreak of the pandemic.

The first stage was marked by the excavation of the Chau Say Tevoda in Angkor, sponsored by China since 1998, and lasting until 2013, to help with the preservation of the site. During this period, the growth in China's overseas archaeological projects was relatively slow and stable. However, the period also witnessed a profound transformation, from the works’ being unknown in the first few years to attracting huge attention more recently. For the first time, these overseas projects acquired a place of their own within the Chinese archaeological community. Except for the Kenyan project, most of the work at this stage was located around China, and culturally there was a close correlation. Even if the Kenyan project was far away in East Africa, it could still be associated with China through Zheng He's voyages.

The second stage began in 2014 and lasted until 2019, a period of rapid development for overseas archaeology. Thanks to the state’s call and policy, as well as its financial support, the number of relevant archaeological projects increased rapidly, with the durations simultaneously extended. The number of projects being undertaken in the same year increased substantially. During this period, some overseas projects actually managed to expand to the hinterland of other civilizations, and methods of examining foreign cultures were further highlighted.

From 2020 until now, we can be said to be in a period of suspension where overseas archaeology is concerned. Relevant fieldwork has basically stagnated, though certain exchange activities are happening in cyberspace. Nevertheless, on the whole, the general momentum of development remains good. With the shift in the Covid-19 policy, activities are expected to gradually resume, leading to new developments ahead.

Speaking of current areas of focus, most of China's overseas archaeological projects are concentrated in neighboring countries, with the largest number being undertaken in Russia. However, in recent years, China has also developed new archaeological projects in some relatively distant countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Honduras, Kenya, Romania, Egypt and others. Among all these, the most representative ones include the archaeological investigations of the Lamu Archipelago in Kenya, the Ming tepe fortification site in Uzbekistan, and the Copán Maya site in Honduras.