As a scholar specializing in Southeast Asian studies, especially on Indonesia and the Malay World (Nusantara) could you please describe the development of Southeast Asian studies overall, particularly in China, and say what Peking University has done to promote these fields of study?

Modern Southeast Asian studies in China can be traced back to the 1920s, when the National Jinan University in Shanghai established the Nanyang Cultural Affairs Bureau to study socioeconomics, history, geography, and social culture in the Southeast Asian region. Southeast Asian studies in China started in the form of ‘Nanyang studies’, was closely associated with research on the Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia and was broadly defined as ‘Overseas Chinese Affairs’. Despite the Second World War having an adverse impact on Chinese research institutions focusing on Southeast Asian studies, interest in and the demand for studying Southeast Asia continued to grow in China. In the post-war era, ‘Overseas Chinese Affairs’ or ‘Nanyang studies’ gradually evolved into ‘Southeast Asian studies’ focusing on the region’s nation-states. At present, research institutions concentrating on Southeast Asian studies in China can be found at institutions of higher learning, Academies of Social Sciences, and military organizations, which are located in cities including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Fujian, Guangxi and Yunnan.

In terms of the history of the field, Southeast Asian studies at Peking University stemmed from two branches: the Department of Oriental Languages, and the Institute of Asian and African Studies. The study of Southeast Asian languages at the Department of Oriental Languages was built upon the disciplinary foundations laid by the National College of Oriental Languages, which had been established in 1942. In the beginning, these languages included Burmese, Vietnamese, and Thai. The objective was to train translators to satisfy the urgent requirements of the nationalist government during the war. In 1949, the National College of Oriental Languages was merged into the Department of Oriental Languages, which gradually added Bahasa Indonesia (Malay) and Filipino to its curriculum. In 1999, the Department of Oriental Languages was integrated with the Departments of English, Russian, and Western Languages to form the School of Foreign Languages. The Department of Southeast Asian Studies, under the School of Foreign Languages, now offers undergraduate and postgraduate programs in all five languages.

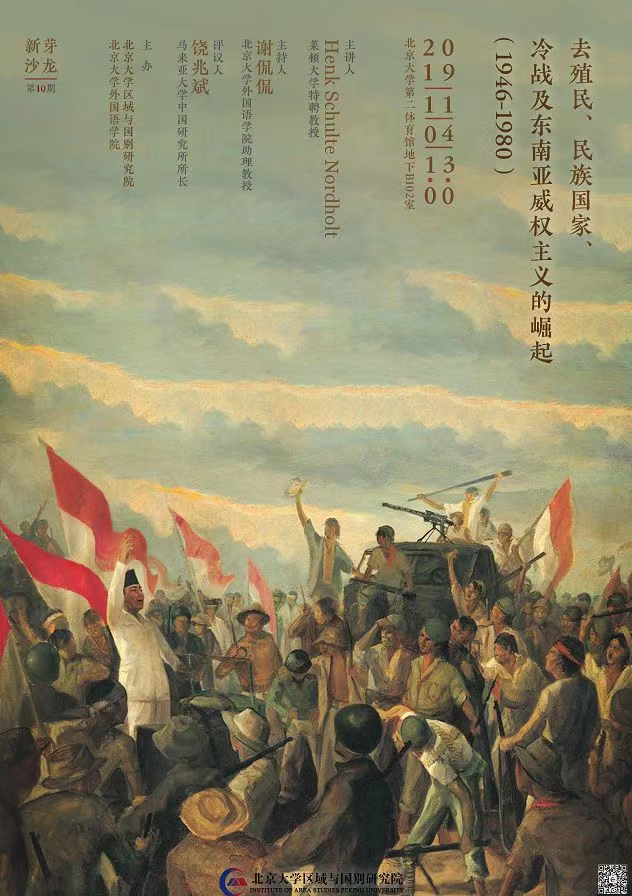

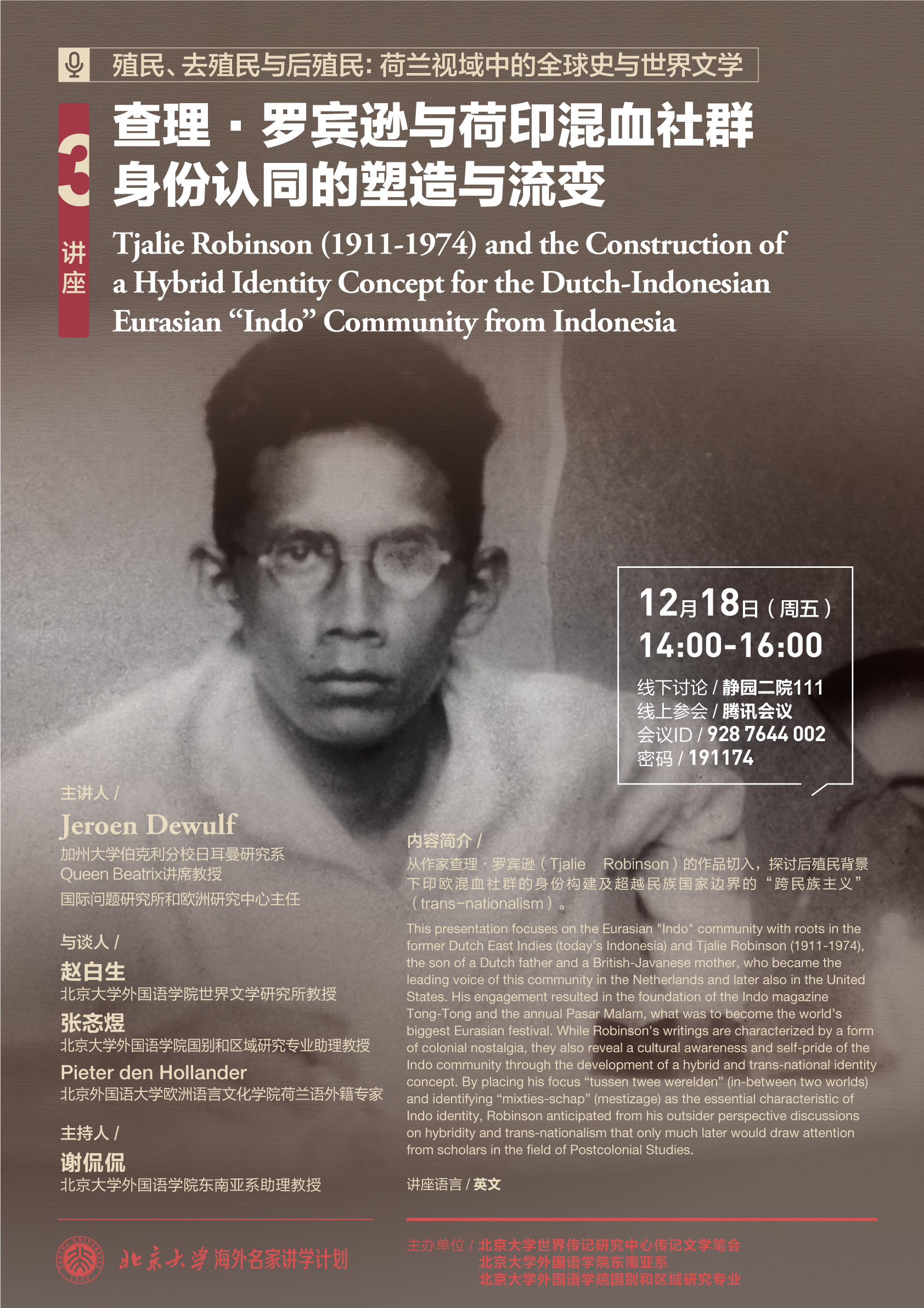

The Institute of Asian and African Studies was set up at Peking University in 1964 with the aim of studying and teaching Asian and African politics, economy, society, and culture and serving China’s diplomatic initiatives. The Southeast Asian Research Unit at the Institute has long focused on the Overseas Chinese, Southeast Asian politics and economy, and other topics. At the end of the 1990s, the Institute of Asian and African Studies was merged with the School of International Relations. Apart from the School of Foreign Languages and the School of International Relations, scholars from other departments at Peking University, such as History, Government, Law and Sociology, have been engaged in the study of Southeast Asia as well. Peking University has also set up cross-departmental and interdisciplinary research institutions, including the Asia-Pacific Research Institute, the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, and the Center for Overseas Chinese Studies. Moreover, in 2018, Peking University established the Institute of Area Studies, of which Southeast Asian studies is an important component, aiming to integrate campus-wide resources and build a comprehensive academic platform that will draw together academic research, academic management, scholarly training, think-tank functions, and international academic exchanges.